A research roundup to show that your office layout is toxic (and some tips for making it better)

24 September 2017

Apple’s new office layout has been described as “programmer hell”. The research backs up this sentiment.

Apple’s new office layout has been described as “programmer hell”. The research backs up this sentiment.

Can you still call yourself a data-driven company if you don’t listen to the data?

I used to think my frustration with open office plans meant that something was wrong with me.

Everyone seemed so bought into the hype about how open layouts create transparency and collaboration. Reducing physical barriers felt so symbolic and positive. No one wanted to argue against these ideals. I, too, wanted transparency and collaboration.

So when I’d have a hard time focusing, I’d tell myself that I just had to try harder. When a coworker would tell me how great it is to be able to randomly tap anyone on the shoulder, I’d nod quietly and retreat to my headphones. I convinced myself that wanting to be able to focus on my work somehow made me less collaborative.

I thought that I needed to embrace the constant interruptions as a source of creativity.

But just because the goals are noble doesn’t mean that open office plans are the correct solution. Open layouts are objectively making us less happy, less productive, and more sick.

In fact, overwhelming evidence points to open offices being detrimental on every account. And while younger workers are often the most vocally supportive of open office environments, studies have shown that workers of all ages are just as negatively impacted.

The longstanding belief that open offices foster better informal interactions and collaboration doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. Rather, studies show that open layouts result in shorter and lower quality discussions than in closed layouts. This is in addition to the detrimental effect of constant distraction.

It seems that physical openness does not equal cultural openness.

All in all, there just isn’t any strong evidence to support the oft-touted benefits of open offices. When you feel overstimulated, unfocused, or frustrated at work, it’s important to remember that it’s not a personal failing on your part.

Research Roundup — Open Office Layouts

In an effort to get us all talking about the actual evidence, below is a summary of 12 major pieces of research about open office plans.

The research will show that:

- Open offices do not increase open communications. Transparency and communication are more complex than just removing physical barriers.

- Open offices cause decreased motivation, decreased capacity for complex or creative thinking, and overall lower productivity.

- Open offices introduce constant distractions into the workplace. A distraction of even 2.8 seconds is enough to cause errors in work when people re-orient to their task. What’s worse is the fact that people aren’t aware that they’re making mistakes or have been affected by the disruption.

- Individuals have low self-awareness of negative outcomes. This shows that people may not always be the most objective judges of their own environments.

- Potential long-term health consequences like hypertension, musculoskeletal disorders, and heart disease could arise from working in open offices. Causes include elevated epinephrine levels, chronic noise exposure, frequent interruptions, and lack of control over personal environment.

- Open offices are blunt, ineffective instruments. But the research offers an abundance of more creative solutions to workplace productivity issues. These could be through better expectation setting, better physical spaces, better processes, and more focus on the varied needs of modern jobs.

I hope this research allows you to advocate for better work environments. For full summaries, keep reading!

Disproving widespread myths about workplace design

Kimball International by the BOSTI Associates, 2001

Summary

BOSTI specializes in analyzing businesses and strategically implementing workplace solutions to match needs of employees and businesses. Their research is rigorous and based on objective methodologies. It was conducted with 13,000 workplace users spanning various industries.

This publication is extensive, and is only a snapshot of a larger book by the BOSTI research group. It focuses on top predictors of performance, and explores the design and facility management practices that can improve them.

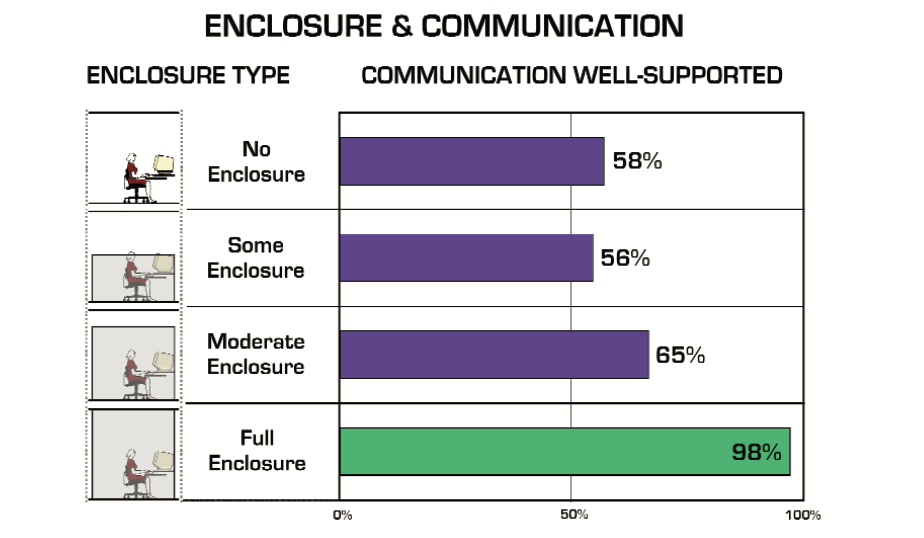

The major finding that was most interesting to me is that open offices don’t increase open communications. The open office plan’s entire premise is based on the assumption that reducing barriers increases the quality of communication between coworkers. However, BOSTI found the exact opposite to be true:

Figure 1. Full enclosures show the best support for quality communications.

Figure 1. Full enclosures show the best support for quality communications.

The document is extensive, so here are some of the most relevant passages:

- A list of workplace qualities that have the strongest effects on individual and team performance and job satisfaction. Some of the qualities like “distraction-free solo work” and “supporting interactions with coworkers” were at the top of the list. Both are important features of productive workplaces. However, open office plans cause them to be in competition with each other.

- A breakdown of how people spend their time, showing that workers spend the majority of their time on focused, quiet work.

- Employees learn the most through informal interactions with coworkers, as opposed to formal classes or training. But current setups often make it challenging to effectively interact with coworkers.

- A list of common assumptions about open offices, explored through relevant research findings. This list goes into alternatives and solutions to common missteps.

- Contrary to most assumptions, high degrees of enclosure actually improve overall communication between coworkers (See figure 1).

- Physical openness does not equal communication openness, and generally has a negative effect.

- What to do with these findings to improve your office environment.

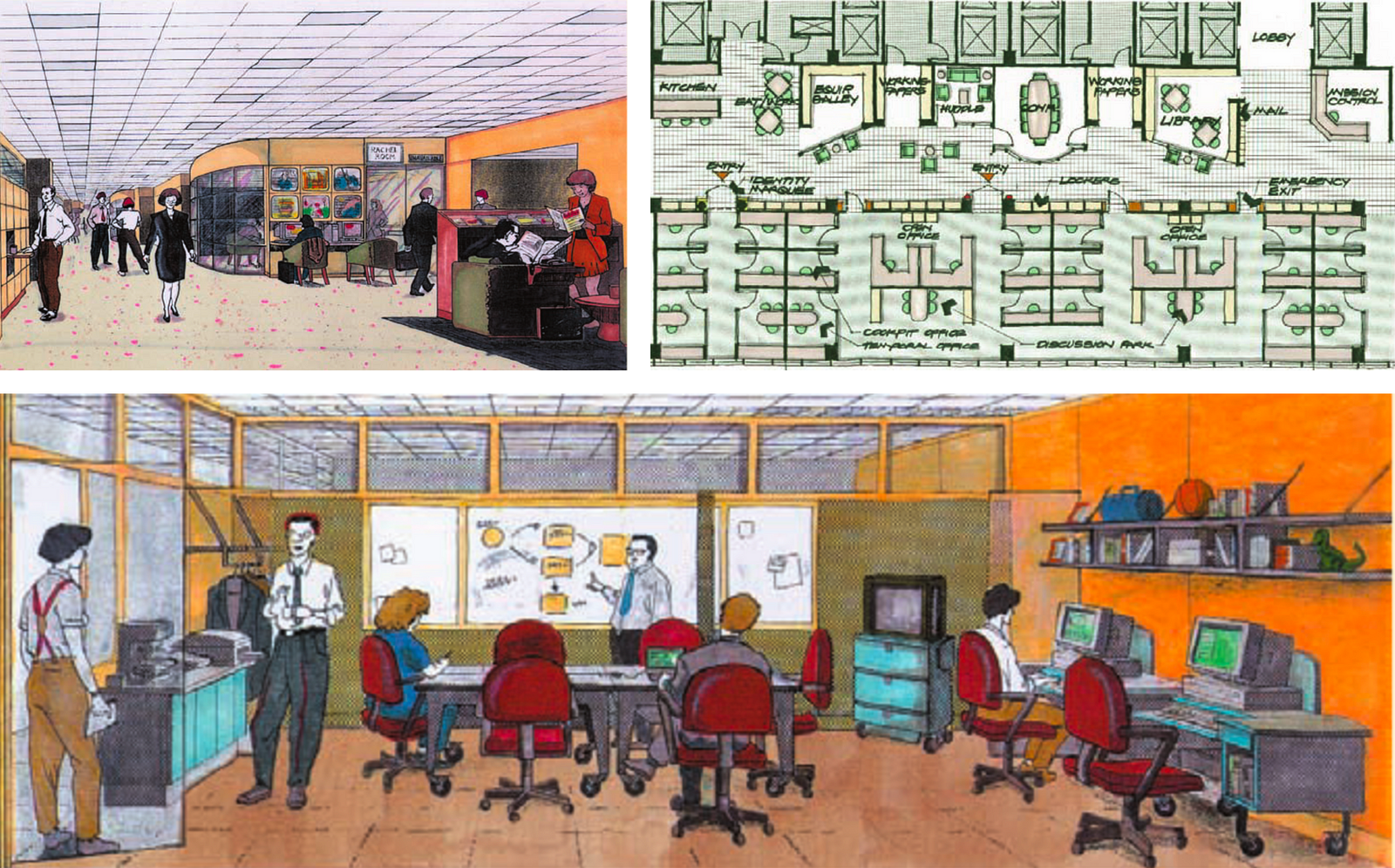

This example of an updated office design includes an interaction-heavy “Main Street” (top left), private workspaces that have physical and auditory blockers, and private group collaboration spaces (bottom).

This example of an updated office design includes an interaction-heavy “Main Street” (top left), private workspaces that have physical and auditory blockers, and private group collaboration spaces (bottom).

Should Health Service Managers Embrace Open Plan Work Environments? — A review

Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 2008

Summary

This paper is a large scale literature review which overwhelmingly shows that open office plans are negative.

“In 90 per cent of the research, the outcome of working in an open-plan office was seen as negative, with open-plan offices causing high levels of stress, conflict, high blood pressure, and a high staff turnover. The high level of noise causes employees to lose concentration, leading to low productivity, there are privacy issues because everyone can see what you are doing on the computer or hear what you are saying on the phone, and there is a feeling of insecurity” (source).

This review was also referred in a variety of articles, like The Scientific American, New York Daily, In The Black, Sourceable, and a couple more.

Stress and Open-Office Noise

Journal of Applied Psychology, 2000

Summary

This study was conducted with 40 clerical workers, divided into two groups. Individuals in both groups were asked to complete basic office clerical tasks during a 3-hour time period. This was followed by the opportunity to solve puzzles.

The control group did their tasks in a quiet atmosphere. The other group worked with simulated open-office noise that played continuously over loudspeakers, falling between 55 dBa and 65 dBA. The simulated noise included “conversation segments, typing sounds, ringing phones, and drawers being opened and closed.”

The research found that low level open office noises resulted in:

- Elevated epinephrine levels (but not norepinephrine or cortisol levels), which shows increased stress.

- Fewer attempts to solve puzzles, showing decreased motivation.

- Fewer attempts to make ergonomic or postural adjustments to their work station, which could result in occupational stress and musculoskeletal disorders.

- Self-reported feelings of stress were the same for both groups. This hinted that individuals may not always be the most objective judges of their own environments.

Chronically elevated epinephrine is a risk factor for heart disease. Hence, the study also touches on potential long-term health consequences from chronic low-level noise exposure.

Workplace Satisfaction — The Privacy-Communication Tradeoff in Open Office Plans

Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2013

Summary

This study is interesting because the authors didn’t actually plan to study open offices going in. They were looking for information on worker satisfaction with office temperatures.

The authors got access to a database of 42,000 responses to a “post-occupancy survey”. The data showed that people who work in open office plans were much less happy with their environment than people in closed offices.

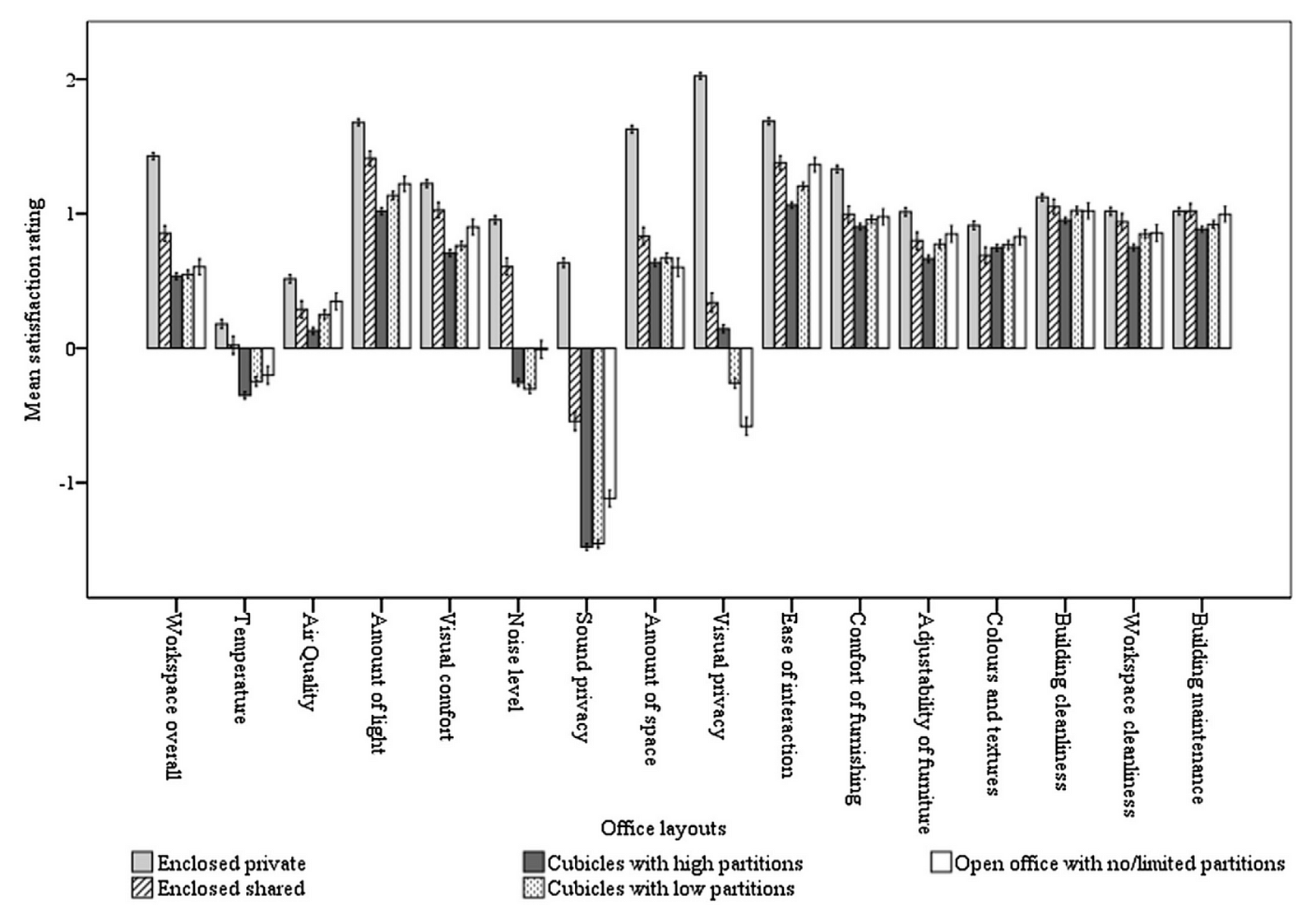

This research turns out to be the largest study of employee satisfaction levels in open offices (source). It specifically analyses employee perception in both closed and open office settings. Occupants assessed Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) issues. They found that — enclosed private offices outperformed open offices in acoustics, privacy, and proxemics. At the same time, the benefits of “ease of interaction” in open offices didn’t outweigh the negative impacts on IEQ.

Not only was noise a major problem in open office settings, but collaboration between coworkers did not improve.

Towards the end of the study, the authors note that these results “categorically contradict the industry-accepted wisdom that open-plan layout enhances communication between colleagues and improves occupants’ overall work environmental satisfaction”.

Mean satisfaction rating (3 = very dissatisfied, through 0 = neutral to 3 = very satisfied) for IEQ questionnaire items by office layout configurations (Error bars = 95% confidence interval).

Mean satisfaction rating (3 = very dissatisfied, through 0 = neutral to 3 = very satisfied) for IEQ questionnaire items by office layout configurations (Error bars = 95% confidence interval).

Traditional versus Open Office Design — A Longitudinal Field Study

Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA), 2002

Summary

This study followed employees of a large oil and gas company as their workplace transitioned from a “traditional office” to an open one. Surveys were conducted before the transition, 4 weeks after, and six months after. Researchers tracked satisfaction with surroundings, stress levels, job performance, and interpersonal relationships.

Even with the longer adjustment period, employees showed negative results on every single measure. Not only was the workplace more disruptive and stressful, coworkers reported feeling more distant and resentful of their coworkers. Overall, they had lower productivity.

Who Moved My Cube?

Harvard Business Review, 2011

Read it: Full article

Here’s an infographic on some of the high level points

Summary

The authors spent the past 12 years conducting nine studies about the effects of design on workplace interactions. These included original research and extensive literature reviews. Overall, they found that workspaces encourage quality interactions when they exhibit a balance of the three Ps: proximity, privacy, and permission.

Proximity

There is evidence that decreased physical proximity results in less frequent interactions between coworkers. But it’s not as easy as just putting people closer together. Thomas Allen, organizational psychology professor at MIT, found that the “social geography” of a space was the most important determinant of quality informal interactions.

Instead of focusing on physical centrality, he suggests organizing office layouts to give employees easy access to functional spaces. Such places could be entrances, elevators, photocopiers, and coffee machines, where informal interactions can take place.

Privacy

This is the point that really flies in the face of accepted open office lore — in order to have higher quality, more frequent informal interactions, workers need to have confidence that they won’t be overheard. Workplaces that allow workers “to control others’ access to [themselves] so that [they] can choose whether or not to interact” are the only ones where truly informal interactions can flourish.

One idea to improve privacy is the concept of an alcove. This can allow people to easily move conversations that started out in the open into a more private space.

Permission

Often, if a workplace doesn’t actively specify it, informal chats over coffee are seen as unproductive and employees will avoid them. Companies that encourage this behavior see a rise in quality informal interactions. For instance, Zappos actively encourages managers to spend 20% of their time on socializing and team building.

While physical work environments need these three Ps, so do virtual ones — although it’s more challenging to codify exactly how to provide that. The article covers a variety of examples of nurturing the three Ps in virtual settings.

The article goes on to discuss how to balance these three principles in order to create a workplace that is flexible with the right interplay of these dynamics. Too much of any one of them can backfire. But understanding the fundamentals allows managers to design more productive work spaces. Take a look at this infographic for some high level tips.

Does working from home work?

National Bureau of Economic Research, 2013

Summary

A Chinese travel website called CTrip ran an experiment for 9 months. During this experiment, they gave their call center employees the option to work from home. Half of them remained in the office as a control group.

The company assumed it would save money on office space by allowing workers to telecommute. Any dip in productivity would be offset by those savings. Instead, they found that at-home workers were happier. They also took fewer sick days, and had lower attrition than their in-office counterparts.

The most surprising finding was that they had much higher productivity. Telecommuters completed 13.5% more calls, equalling almost an entire extra work day per week.

There was some level of self-selection in this experiment, which should be considered. One finding was that allowing employees to choose where to work resulted in the best outcomes, since some employees didn’t enjoy working from home.

With call center workers, the work is easy to measure and easy to perform in a remote environment. In general though, there are many factors in determining how effective remote workers might be. The author talked about the need for more research into creative fields. However, he still advocates for allowing one to two work from home days per week (source).

This experiment shows that the common assumption that telecommuters are less productive is often false, and allowing for flexible work from home options can increase employee happiness as well as revenue.

The Physical Environment of the Office: Contemporary and Emerging Issues

International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2011

Summary

This publication was put together by organizational psychologist Matthew Davis. It is a 37-page review of over a hundred studies about office environments. He found that open offices often foster symbolic cohesion. Many employees reported feeling positively about what they represent.

At the same time, these layouts also have negative results in terms of worker attention spans, productivity, creative thinking, stress, motivation, and actual satisfaction.

The publication is organized into the following sections:

- History: A background on open office plans and the research associated with them.

- Iterating on open offices: An overview of the ways open office plans are evolving to suit the growth of knowledge work. This includes a variety of suggestions and case studies for creating effective, flexible workspaces.

- How to facilitate change: The publication includes an extensive discussion about how to facilitate physical changes in the workplace, so as not to “breed resistance and resentment”. It also discusses how to incorporate user participation and bi-directional sharing of information. This section includes two case studies of successfully enacting change through user participation.

- Relying on research: Advice on using existing research from a variety of fields to inform decisions and help facilitate change, and recommendations for new research.

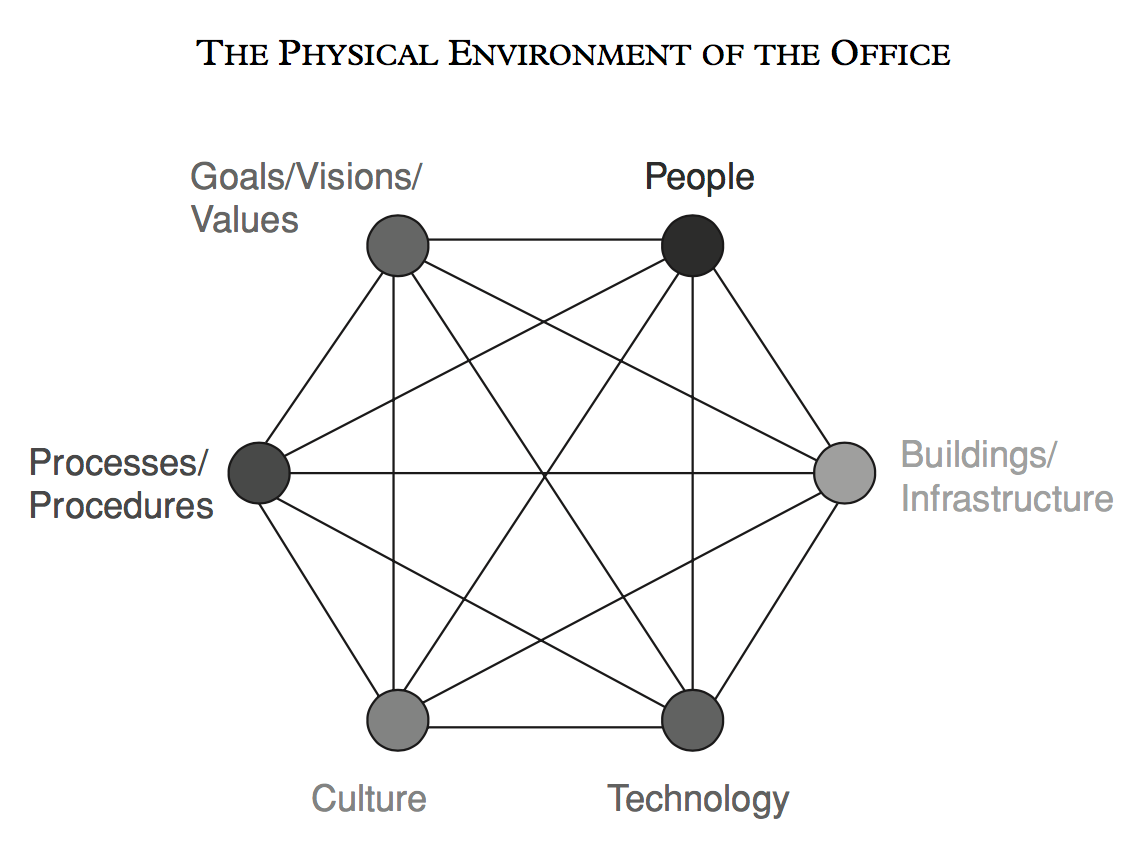

Figure 1. Showing the “inter-related nature of an organizational system”

Figure 1. Showing the “inter-related nature of an organizational system”

One of my favorite parts is the recommendation to not only use socio-technical systems theory to address the physical workplace environment. But also to expand the methodology to account for the entire work culture, including processes (See Figure 1).

A couple of useful passages —

“Whilst useful in supporting knowledge working, [open office layouts] remain a relatively blunt tool, as it fails to acknowledge the variety of tasks that modern knowledge workers may be involved in, the distributed nature of their interactions, and the shifting temporal nature of their roles and tasks.”

“Becker and Steele (1995) observe that it is necessary for organizations to provide areas that allow workers to meet informally if intra- and inter-team collaboration is to flourish. This goes beyond simply removing office walls and partitions, or seating colleagues closer together; rather, the focus is upon designing a variety of spaces that can help to foster the types of interactions desired, in addition to allowing space for more individualistic tasks. […] Furthermore, flexible workspace and easy access to meeting rooms have been related to higher job satisfaction and group cohesiveness”

Sickness absence associated with shared and open-plan offices — a national cross sectional questionnaire survey

Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment, and Health, 2011

Summary

This report’s authors aimed to study any differences in absences due to sickness — between employees working in open office plans and those in single-occupancy spaces.

For this study, researchers conducted surveys with over 2,400 employees spanning over 2,000 offices in Denmark. They categorized offices based on the self-reported number of occupants in a single work room. Participants were 18–59 years of age and results controlled for “age, gender, socioeconomic status, BMI, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, and physical activity during leisure time.”

The study found that absences due to sickness were highly related to the number of office occupants. Individuals in these settings comprised of more than 6 occupants reportedly taking 62% more sick days than their counterparts in single-occupancy workspaces.

The study authors acknowledge that the surveys can only show correlation, but reviewed other literature to shed light on some possible explanations:

- Higher exposure to noise in open offices can cause higher rates of sickness absence. Some limited research draws connections between noise exposure and hypertension or sleep disturbance.

- Another study shows connections to the elevated stress hormones of people in open office layouts.

- Workers in open office spaces are more likely to be exposed to coworker viruses.

- There are many psycho-social effects due to lack of privacy in open office plans. Such effects decrease individual autonomy and makes the worker more reactive to the environment. This is also related to burnout, which can cause absences and sickness.

The cost of interrupted work — more speed and stress

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2008

Summary

This study wanted to measure the disruption cost of interruptions. It also wanted to measure possible differences in disruption costs on different personality types. The goal was to use the findings to inform better system design and help people manage interruptions more effectively. One type of disruption cost is the time it takes to reorient back to the task at hand after an interruption.

Findings include:

- The disruption cost is the same whether or not the interruption was related to the task at hand. Although, the perception is that related interruptions are beneficial.

- A surprising finding is that interrupted work is often performed faster than uninterrupted work. When interrupted, workers develop a mode of faster work (like writing less) to compensate. As a result, they experience “higher workloads, more stress, higher frustration, more time pressure, and effort.

- The study tracked two personality metrics — “openness to experience” and the “need for personal structure”. Scoring high on either metric resulted in the ability to handle interrupted work quicker. The authors note that “perhaps those who need personal structure are better able to manage their time when interrupted.”

The report ends with some recommended next steps in systems design. One suggestion is to use technology to track and control interruptions over long time periods.

Momentary interruptions can derail the train of thought

Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2014

Summary

This study took 300 volunteers and asked them to complete a complicated computer task. This task required them to constantly remember where they were in a sequence.

Researchers interrupted the sequence with side tasks, and found that an attention shift of only 2.8 seconds was enough to mess up the sequence. When the interruptions were at 4.4 seconds, the error rate tripled.

The most disturbing finding was that while participants were distracted and making mistakes, they didn’t exhibit any sort of lag time when reorienting back to the computer task. This means that people don’t know when they’re distracted and can make (potentially catastrophic) mistakes with no awareness.

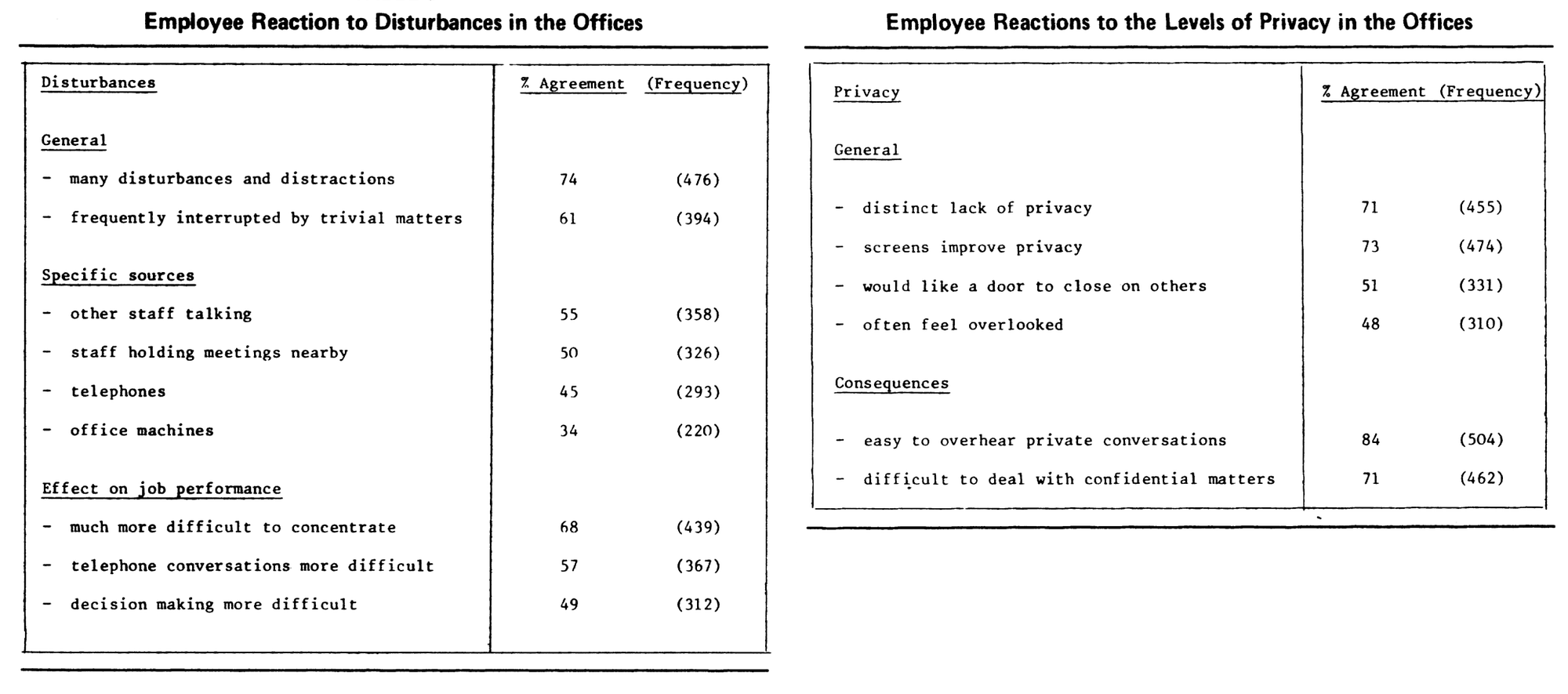

The Open-Plan Office: A Systematic Investigation of Employee Reactions to Their Work Environment

Environmental Design Research Association, 1982

Summary

I added this report not only because it’s a good study, but because it dates back to the early 1980s. It shows that we’ve known how detrimental open offices are from the start.

It also provides some insight into the uniquely negative impacts on people with managerial and technical jobs over those with clerical jobs. Although, every role shows high rates of adverse reactions.

The study followed 649 employees of a Metropolitan County Council. This government office uses a corporate management structure to disseminate and collect information systematically. If assumptions about open offices are correct, this is the perfect structure to benefit from them.

Staff were asked to complete a questionnaire with 96 statements about different aspects of their office environment. There were also some personal and open-ended questions.

Some results include:

- Women reported office temperatures being too cold at much higher rates than men. One floor showed the difference as 64% women reporting it was too cold versus 31% of the men. It is unclear if this is due to basic sex differences or differences in the clothing worn by men and women.

- People reported frustration with both disturbances and the low level of privacy — mostly because of coworker behavior. This suggests that the answer may be in modifying behavior as well as the environment.

- When asked if open office plans create a lack of privacy, people who had only ever worked in large open office plans were less likely to agree with the statement (57%) than those who had worked in smaller offices (74%).

- Most people who had worked in both large open offices and smaller environments preferred the smaller environment (72%).

Table 1 (left) and Table 2 (right)

Table 1 (left) and Table 2 (right)

A result I found interesting is that employees felt that open offices helped them “get on well with colleagues” and facilitated some level of after-hours socialization. This wasn’t enough to make the work itself less stressful.

Personally, I’m not convinced that hanging out with coworkers outside of work hours is an effective goal, nor is it an incredibly inclusive work expectation.

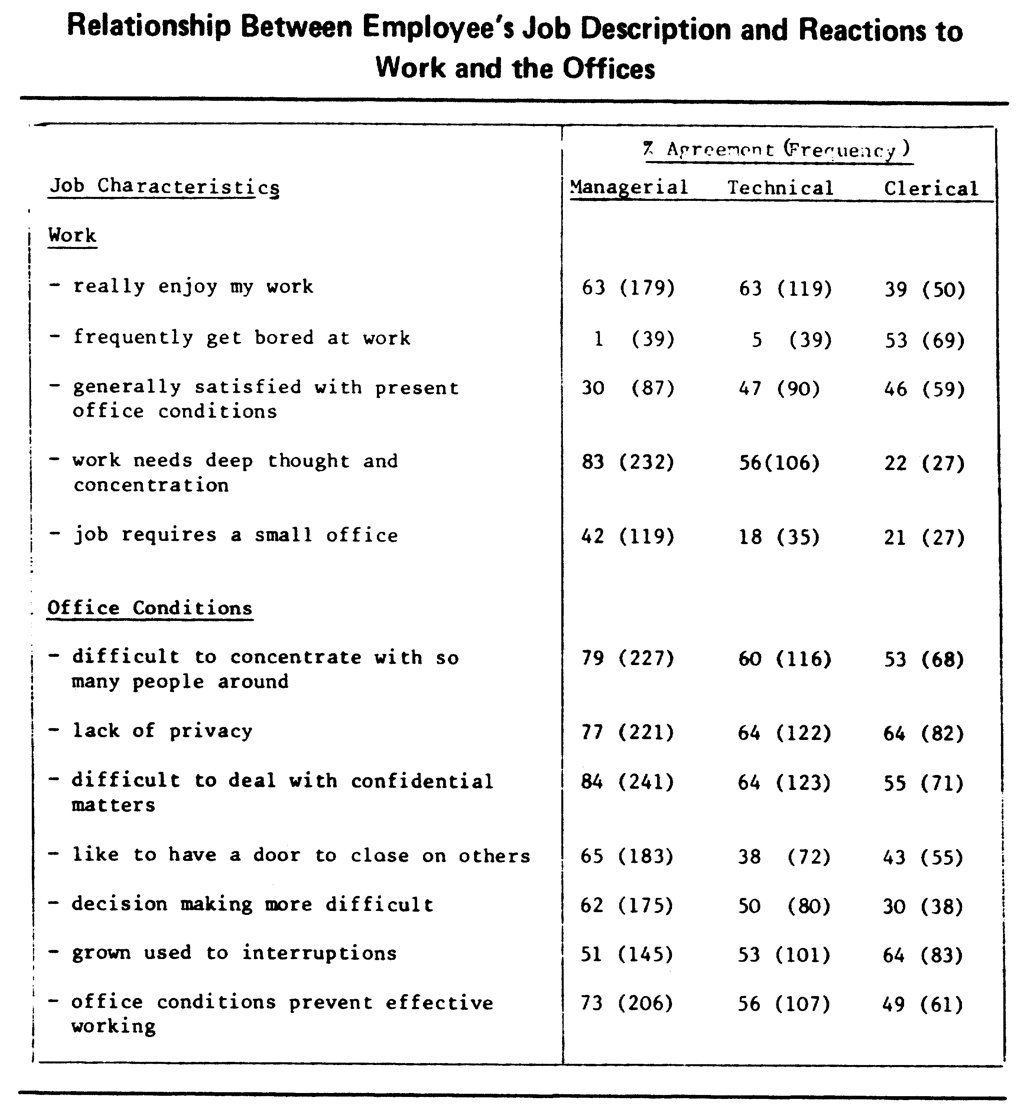

Table 3

Table 3

The study discussed the challenges with defining “productivity” for different types of jobs. It also tried to codify job types and correlate them to reactions to open office plans (see Table 3).

People with jobs that require more deep thought and concentration showed a much higher preference for small offices, and high sensitivity to lack of privacy and number of interruptions.

In fact, “no evidence was found to support the claim that open-planning leads to any improvements in productivity, but rather, if anything, the reverse.”

Privacy at Work: Architectural Correlates of Job Satisfaction and Job Performance

The Academy of Management Journal, 1980

Summary

This is another study dating back to the early 1980s, showing just how long research into open office plans has existed. This report covers three studies that look at the relationships between physical and psychological privacy, job satisfaction, and employee performance. Special attention was paid to the difference between more complex jobs and routine jobs like secretarial work.

It was one of the first studies to really look at the relationship between physical settings and interpersonal behavior. The study was done using prior research work in social and environmental psychology.

The studies looked at people with varying levels of complexity in their jobs. The hypothesis was that — people with less complex jobs (consisting of repetitive work) may benefit from the social stimulation of open office plans.

Some findings include:

- All three studies showed that architectural privacy was associated with psychological privacy.

- Basically no correlation was found between the more open spaces and increased social interactions, except with supervisors.

- Surprisingly, heightened interactions with supervisors (in the more open layouts) didn’t result in better job evaluations. Higher levels of enclosures, however, did correlate to better job evaluations.

- Both groups — people with complicated jobs and people with more routine jobs—reported preferring privacy over accessibility.

This report studied a lot of correlations and resulted in less information about potential causation. But it provided a good basis from which future research was built on top of.

Final thoughts

There is overwhelming evidence that existing versions of open office plans are toxic and ineffective. With this, I’d like to pose a question to all organizations with open layouts who pride themselves in being forward thinking, data-informed, progressive, productive, and want to be profitable —

Can you still call yourself a data-driven company if you don’t listen to the data?

And for everyone else, remember — you aren’t broken, but your office might be.